Monday, 1 February 2016

Minds mirror one another.— the appropriate unit of analysis for psychological science may be two or more persons in relation to one another

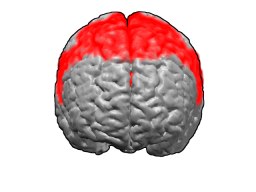

Over two decades ago, publications by Meltzoff & Moore ( 1977) alerted the scientific world to a startling fact about newborn babies: they can imitate the facial and manual actions of other people, actions such as mouth-opening, tongue protrusion and finger movements. It seems that infants have an inborn propensity to ‘match’ their actions and expressions to other people's bodily gestures. A recent neuroscientific gloss on this discovery is that in the premotor cortex of macaque monkeys there exists a type of cell — the mirror neuron — that fires during the execution and observation of mouth and hand actions ( Gallese & Goldman, 1998). Functional magnetic resonance imaging with human subjects has provided corroborating evidence for a mechanism directly mapping observed actions onto internal motor representations of those actions ( Iacoboni et al, 1999). In other words, we primates have ways of perceiving others' actions — and, by extension, expressions of subjective states — that recruit our own tendency to enact or experience those actions or states ourselves. Minds mirror one another.

When it comes to prompting people to think creatively about human psychology, a neurofunctional picture can be worth a thousand psychoanalytical words. The ‘mirror neuron’ perspective on social co-action may be simple, but behind it looms another, more-subtle vision of interpersonal coordination: perhaps human beings are in a state of constantly shifting identification with each other, as the forms of one person's own activity and attitude influence those of someone else. Controversial, yes — but implausible, no. Just as our brains are linked with each other through the activity of neurons, so our minds are linked through an interplay of subjective states ( Trevarthen & Aitken, 2001). In the words of John Donne, ‘No man is an Island, entire of it self’. Set this simple but profound fact in the perspective of early development, and the social transactions that shape children's earliest representations of themselves vis-à-vis other people, and one arrives at a view of mental functioning that gives the interpersonal dimension new prominence.

My point is not that the developmental or neuroscientific evidence establishes the truth of psychoanalytical propositions about the pervasiveness of identification in the emotional transactions between one person and another. Nor does it justify claims about the role of such processes in the development of personality. Rather, such evidence prompts critical re-evaluation of psychological theories that are predominantly individualistic on the one hand or imperialistically cognitive on the other. It suggests a foundational role for a system of self in relation to other. We may need to recognise that for certain purposes — not least, for explaining how people develop abnormal states of mind, and how they come to reflect upon their own and others' mental states — the appropriate unit of analysis for psychological science may be two or more persons in relation to one another (Vygotsky, 1962; Hobson, 2002).

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment